by Linda McLeod and Shelby McGowan

Did the bar for consent agreements at the USPTO just get a lot higher?

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board’s (“TTAB” or “Board”) recent precedential decision in In re Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla, 2025 USPQ2d 1291, 2025 WL 2953731 (TTAB Oct. 14, 2025), offers important guidance on how the Board evaluates consent agreements submitted to overcome likelihood of confusion refusals under Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act. The decision makes clear that generalized and bare-bones consent language—without specific marketplace details—may be insufficient to overcome a §2(d) refusal.

The General Standard for Consent Agreements

Consent agreements are analyzed under the DuPont likelihood-of-confusion test’s tenth factor, which examines the nature of the market interface between the parties. See In re E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 476 F.2d 1357, 1361 (CCPA 1973). The Board and Federal Circuit assess consent agreements on a case-by-case basis considering the following five non-exhaustive guidelines:

- Whether the consent shows an agreement between both parties;

- Whether the agreement includes a clear indication that the goods and/or services travel in separate trade channels;

- Whether the parties agree to restrict their fields of use;

- Whether the parties will make efforts to prevent confusion, and cooperate and take steps to avoid any confusion that may arise in the future; and

- Whether the marks have been used for a period of time without evidence of actual confusion.

“More detailed agreements” weigh “substantially” against a likelihood of confusion, whereas “naked” agreements “carry little weight.” 2025 WL 2953731, at *9.

The Mystic Krewe Case at a Glance

Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla (“YMKG”) applied to register GASPARILLA for drinkware and apparel. The USPTO refused registration based on likelihood of confusion with GASPARILLA TREASURES, a registered mark owned by EventFest covering overlapping goods, including drinkware and clothing.

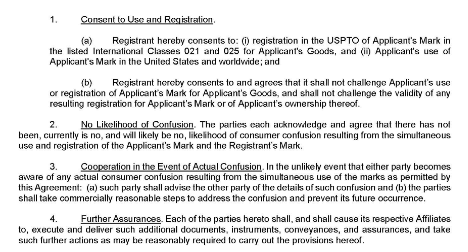

In response, YMKG submitted, among other arguments and evidence, a consent agreement executed by both parties. The consent agreement contained the following core provisions:

The examining attorney rejected the consent agreement, concluding it lacked sufficient details to demonstrate that confusion would be avoided in the marketplace.

The TTAB’s Analysis

On appeal, the Board reiterated that “the more information that is in the consent agreement as to why the parties believe confusion to be unlikely…the more we can assume the consent is based on a reasons assessment of the marketplace, and consequently the more weight the consent will be accorded.” 2025 WL 2953731, at *7. Because the “brief” one-page agreement failed to address the period of simultaneous use of the marks without confusion, the parties’ channels of trade or fields of use, or the actual manner of use and display of the marks involved, the Board agreed with the examiner and concluded that “there is no sufficient basis in the consent agreement explaining why confusion is unlikely where identical and legal identical goods are sold to identical potential consumers in identical channels of trade under highly similar marks.” Id. at *11

In short, the consent agreement did not rise to the level of a “more detailed” agreement, and accordingly weighed “only slightly” against a likelihood of confusion. Id. The Board ultimately affirmed the 2(d) refusal based on the overwhelming weight of the other DuPont factors including highly similar marks and legally identical goods and trade channels.

Consent Agreement Terms Post-Mystic Krewe

In the wake of Mystic Krewe, Applicants and practitioners should consider adding the following terms to distinguish the parties’ respective marketplaces and increase the chance that a consent agreement will be given substantial weight in the likelihood-of-confusion analysis.

- Duration of Concurrent Use Without Confusion

Identify the approximate length of time the parties have used their respective marks simultaneously without evidence of actual confusion. - Clarification of the Relationship Between the Goods or Services

Include a statement that the goods or services are not identical or not legally identical, rather than leaving that point implicit. Provide distinguishing details about the goods or services covered by the involved application and registration. - Specific Channels of Trade and Fields of Use

Include a statement regarding any distinctions in trade channels or fields of use for the involved goods or services, and add terms explaining steps to maintain those distinctions going forward. - Differences in Presentation and Use of the Marks

Where applicable, explain how the marks differ in actual use—such as the inclusion of additional wording, use with a house mark, or incorporation of distinctive logo elements.

Conclusion

Although Mystic Krewe involved highly similar marks and legally identical goods, the decision reflects a broader expectation that consent agreements must contain meaningful, fact-based terms explaining the marketplace distinctions between the parties, the marks, and goods/services, and trade channels. This decision signals that the TTAB will more closely scrutinize whether an agreement provides concrete information showing how the parties have avoided—and will continue avoid—confusion in the marketplace.

As a practical matter, however, parties should remember that consent agreements are publicly filed. A successful consent agreement will provide enough substance to satisfy the USPTO while protecting sensitive business positions.